What is Star Wars Canon?

Star Wars canon is a consistently growing collection of recognized works that make up the official storyline of Star Wars, including movies, TV series, novels, comics, and video games.

George Lucas initially established canon to consist of the first six Star Wars films and the content he developed and produced for Star Wars: The Clone Wars.

These stories are regarded as the fixed points of Star Wars history, the characters, and events that all other stories must align with.

Overview

Starting in the 1990s, Lucasfilm Ltd. licensed a large array of interconnected narratives produced by various authors, including comics, novels, and video games, which became known as the official Star Wars Expanded Universe.

This universe existed alongside the version directly overseen by Lucas. The Expanded Universe was described as “quasi-canon,” while Lucas’ version was seen as the definitive canon or the “only true canon” among varying levels of canon.

In 2000, Lucas Licensing developed an internal database to catalog and manage the fictional elements of the Star Wars universe, establishing a tiered canon system.

At the top of this hierarchy were George Lucas’ original vision—the six films and Star Wars: The Clone Wars.

Below this was the Expanded Universe, which Lucas Licensing supervised at a lower level of canonicity. Additionally, the company organized these elements into distinct publishing eras.

Following The Walt Disney Company’s acquisition of Lucasfilm on 2012, the Expanded Universe was rebranded as Legends.

As a result, the term “canon” was reserved solely for George Lucas’ original canon—the six movies and the seasons of Star Wars: The Clone Wars that he personally developed and produced—along with all movies, television series, comics, novels, video games, and toys produced by Lucasfilm after the acquisition, including the Sequel Trilogy and beyond.

How the Concept of Canon has Evolved Over Time?

The concept of Star Wars canon evolved from its initial establishment in 1994, where it included films, screenplays, and certain licensed works, to the development of a hierarchical canon system by the early 2000s, and ultimately, to the redefinition of canon after Disney’s acquisition of Lucasfilm in 2012.

Early Canon Concepts: Establishing the Foundations (1994-2000)

The concept of Star Wars canon was first established in the fall of 1994, in the debut issue of Star Wars Insider, a Lucasfilm magazine.

Production Editor Sue Rostoni and Continuity Editor Allan Kausch defined “gospel” or canon as including the screenplays, films, radio dramas, and novelizations, all originating from George Lucas’ original stories.

Other works, authored by various writers, were also considered part of the continuity, with the collection of published works forming a vast, mythological history with many offshoots and variations.

In March 1994, A Guide to the Star Wars Universe (second edition) by Bill Slavicsek introduced a coding system that categorized Star Wars content.

The Original Trilogy and its adaptations were considered “original Lucasfilm source,” while approximately seventy other works, including The Thrawn Trilogy and Dark Empire, were labeled as “officially licensed sources.” These sources may not always align with George Lucas’ vision of the galaxy.

In the 1994 reprint of Splinter of the Mind’s Eye, Lucas reflected on how the Star Wars universe had grown beyond his original story, acknowledging the contributions of other writers.

He remarked that although his films told one story, many more stories were being created by others, inspired by the universe he had crafted.

By 1996, The Secrets of Star Wars: Shadows of the Empire, written by Mark Cotta Vaz, introduced the idea of two different canons: one being a timeline curated by Lucasfilm’s continuity editors, and the other consisting of core works like screenplays and novelizations.

Allan Kausch clarified that while the continuity team maintained a “Canon” of major events and character timelines, more peripheral material, like the old Marvel Comics, was not always incorporated into continuity.

In 1998, The Star Wars Encyclopedia by Stephen J. Sansweet further formalized this distinction, emphasizing that the Special Edition of the Original Trilogy, as well as authorized adaptations like novels, radio dramas, and comics, were canon. Beyond these, other materials were classified as “quasi-canon.”

In the August/September 1999 issue of Star Wars Insider, George Lucas explained that while he maintained creative control over his films, he could not oversee the entirety of the expanding Star Wars universe.

Establishing a Canon Hierarchy (2000-2008)

In January 2000, Lucasfilm brought Leland Chee on board to create an internal database for the Lucas Licensing Publishing department, which was called the Holocron.

This database replaced the previously used “bibles” for tracking and organizing all Star Wars fictional elements, introducing a hierarchical system with different levels of canon. Each entry and source included a canon field.

“G” canon referred to George Lucas’ canon, originally including the six Star Wars films and unpublished internal notes from Lucas or the production team.

“C” canon, standing for continuity, encompassed licensed properties such as most of the Expanded Universe, while “S” canon, for secondary, referred to works created before Lucasfilm ensured internal consistency in the Expanded Universe. “N” canon, for non-continuity, was reserved for clear contradictions.

In April 2000, a post on the official Star Wars forums by Sansweet further clarified the distinction between canon and quasi-canon, referencing different levels of canon but emphasizing that the films were the only true canon.

In June 2001, the fourth issue of Star Wars Gamer discussed what was considered canon within the Star Wars universe.

Later, in Star Wars Gamer issue 6 (August 2001), Sue Rostoni defined canon as an authoritative list of books compiled by Lucas Licensing editors.

The goal was to present a continuous and unified history of the Star Wars galaxy, as long as it did not contradict or undermine George Lucas’ films and screenplays.

On August 17, 2001, when asked about what constituted canon, Sansweet pointed to a statement by Christopher Cerasi, which highlighted that the films represented absolute canon—the core story of Star Wars.

While novelizations stayed mostly true to Lucas’ vision, small differences existed due to the writing process.

He also acknowledged that as one moved further from the films, more room for interpretation and speculation existed, leaving room for artistic variation across different mediums.

In August 2001, Star Wars Insider issue 57 reiterated that the films were the one true and absolute canonical source.

In a 2001 interview later published by Cinescape in July 2002, George Lucas explained that he had no plans for a third trilogy, and any continuation of the saga would exist within licensed properties.

He described two distinct “worlds” or “parallel universes”—his world, which consisted of the films, and the other world, which he referred to as the licensing world of books, games, and comics.

He noted that these two worlds didn’t overlap, as his films covered a specific period of time, while licensed properties filled in gaps between them.

In May 2003, the official Star Wars forums saw a discussion about canon after Star Wars Insider issue 68 claimed that David West Reynolds’ Incredible Cross-Sections books would be canonized.

Leland Chee clarified the difference between Lucasfilm’s canon, which included everything produced by the company (films, books, games, internet content), and movie canon, which was restricted to the films themselves.

Sue Rostoni also acknowledged that while canon could be confusing, it had a clear hierarchy, with films, novelizations, and radio dramas at the top.

In June 2004, Rostoni confirmed that George Lucas did not typically contribute ideas to the Expanded Universe.

He only reviewed story concepts or ideas when it involved sensitive areas or characters he created, but otherwise, he regarded the Expanded Universe as separate from his Star Wars.

In August 2004, Chee responded to a question about whether C-canon and G-canon represented independent canons, affirming that they formed part of one overall continuity.

In August 2005, George Lucas reiterated in an interview with Starlog magazine that he didn’t read Expanded Universe content, confirming his earlier statements about the two separate worlds or universes, and noting the potential for inconsistencies between the films and the Expanded Universe.

In December 2005, Chee clarified that while Lucas wasn’t bound by the Expanded Universe, he was open to using elements from it, such as Aayla Secura and the name “Coruscant.”

In November 2006, Chee addressed a fan debate about the existence of two official continuities—one solely based on the films, and one that included the Expanded Universe—confirming that both existed.

He noted that fans could decide which continuity they preferred, as disregarding either group would be unfair.

Chee also clarified that Cerasi’s “foggy windows” metaphor referred to the combined continuity of the films and Expanded Universe, not just film-only continuity. Anything not in the current version of the films was irrelevant to the film-only canon.

Six Canon Levels, Three Pillars, and Two Different Perspectives (2008-2014)

In February 2008, Howard Roffman, President of Lucas Licensing, addressed the issue of canon while discussing the marketing strategy for Star Wars: The Clone Wars TV series.

He emphasized that the company had maintained a clear branding approach for the past decade, ensuring that all materials contributed to the overall Star Wars lore while keeping the story unified under the Star Wars saga.

In March 2008, at the ShoWest conference, George Lucas clarified his perspective on Star Wars canon. For him, the story didn’t extend beyond Anakin Skywalker’s arc.

While acknowledging the existence of books featuring characters like Luke Skywalker after Episode VI, Lucas stated that these belonged to the “licensing world,” separate from his vision.

He identified three distinct “worlds”: his own, the licensing world, and the fans’ world. He highlighted that these worlds don’t always align.

By May 2008, Lucas further articulated this idea by comparing the Star Wars franchise to the Trinity in Christianity, identifying three “pillars”: himself as the father, Howard Roffman as the son, and the fans as the holy ghost.

He noted that while these pillars don’t always align, his control remained over the movies and TV shows.

He reiterated that there would be no more feature films beyond Episode VI, framing the saga as the tragedy of Darth Vader.

In subsequent interviews, such as one with Los Angeles Times on May 7, Lucas restated that Star Wars ended with Return of the Jedi, and there was no further story to tell beyond the Skywalker family’s redemption arc.

On May 8, 2008, Leland Chee, an archivist at Lucasfilm, confirmed that The Clone Wars TV series would not be part of the Expanded Universe, but would hold the same level of canon as the films.

He clarified that T-canon, which included TV productions, stood separate from the Expanded Universe and shared the same “pillar” as Lucas’ films.

In Star Wars Insider issue 104, published in September 2008, Lucas reiterated the scope of his work: he was responsible for the films and TV shows, while the licensing group managed books, games, and other materials. The distinction between the Expanded Universe and Lucas’ direct creations became more defined.

By December 2008, Dave Filoni, supervising director of The Clone Wars, explained that Lucas regarded his films, the animated series, and the planned live-action TV show as part of official canon.

Filoni frequently consulted Expanded Universe material but deferred to Lucas on what could be integrated.

In 2009, Filoni emphasized the difference between Lucas’ canon and Expanded Universe stories.

For example, General Grievous’ backstory, explored in the comics, was not considered part of the official canon but simply a possibility.

Henry Gilroy, a writer for The Clone Wars, clarified that although the Expanded Universe introduced many ideas, only Lucas’ creations were considered true canon, with everything else falling under the Expanded Universe banner. His work took precedence over any previously established EU content.

In 2010, Daniel Wallace discussed the uniqueness of Star Wars canon in comparison to other franchises like Batman, where multiple canons exist across different media.

In Star Wars, Lucas had the authority to override anything in the publishing universe.

Pablo Hidalgo, an Expanded Universe writer, in November 2010, compared the release of The Clone Wars to the introduction of the Prequel Trilogy in 1999.

Both were seen as Lucas’ definitive interpretation of the Star Wars universe, which sometimes conflicted with the Expanded Universe.

By October 2011, Lucas expressed in an interview with SciFiNow that he viewed The Clone Wars series as an extension of the films, simply a different format for telling larger stories, but all part of the same overarching narrative.

Leland Chee, in 2011, explained the distinction between Lucas’ vision, which encompassed the films and The Clone Wars, and the vision of Lucas Licensing, which governed the Expanded Universe. These two perspectives were distinct and did not always align.

In Star Wars Insider issue 134, published in June 2012, Dave Filoni stressed that while the Expanded Universe could inspire the official canon, it remained separate from Lucas’ direct creations.

The writing process for the TV series often took inspiration from the EU, but there were clear distinctions between the visual medium and published works.

By October 2012, in The Essential Reader’s Companion, Pablo Hidalgo reaffirmed that the most definitive canon lay within the films and TV shows in which George Lucas was directly involved.

The Disney Era: Redefining Canon and Introducing Legends (2014-present)

Walt Disney announced its acquisition of Lucasfilm on October 30, 2012, with the deal finalized on December 21, 2012.

In preparation for new Star Wars films, Lucasfilm rebranded the Expanded Universe as Legends on April 25, 2014.

From then on, the term “canon” referred solely to George Lucas’ original vision—comprising the six original films and the seasons of The Clone Wars that he personally developed.

It also included all movies, TV series, novels, comics, toys, and video games produced by Lucasfilm after the acquisition.

After this decision, the only previously published material still considered canon includes the six original films, novels that align with on-screen content, The Clone Wars TV series and movie, and Part I of the short story Blade Squadron.

Any material released after April 25, 2014, such as Star Wars Rebels, along with all Marvel Star Wars comics and novels starting with A New Dawn, is part of the new canon.

The newly established Lucasfilm Story Group now manages this continuity. Characters from the Legends continuity can still be used, though their previous stories are no longer canon.

On September 29, 2018, Matt Martin from the Lucasfilm Story Group announced on Twitter that the tiered canon system, first introduced by Leland Chee in the early 2000s, was no longer being used.

However, Episodes I-VI and The Clone Wars still retain the highest level of canonicity in cases of contradictions.

In March 2018, Howard Roffman discussed Lucasfilm’s previous canon policy, explaining that the team aimed to keep all content consistent with each other and the movies, which were considered canon.

However, George Lucas, as the creator, often made changes that overruled the spinoff fiction and game program, creating an alternate universe.

Roffman also noted that under Lucas, there were frequent debates when conflicts arose between the Expanded Universe and new material, but ultimately Lucas had the final say.

Now that a single committee controls everything, a unified canon can be maintained.

Maintaining a seamless canon created by multiple authors and directors has proven difficult.

For example, the premiere of The Bad Batch, titled “Aftermath,” directly contradicts events depicted in the Star Wars: Kanan comic series about the Battle of Kaller.

On May 7, 2021, Pablo Hidalgo addressed this discrepancy, suggesting that fans view canon as akin to a history textbook that dramatizes events for the medium in which they are presented.

Notable Exceptions

The following material, despite being released after April 25, 2014, is not part of Star Wars canon:

- Star Wars: The Old Republic (video game)

- LEGO Star Wars products and media

- The Darth Vader and Son series (2012-2021)

- The Old Republic-related short stories published on the developer’s blog

- Comic strips published in Star Wars Comic UK issues #5-#13 (2014)

- The Phineas and Ferb: Star Wars TV special (2014)

- Dark Horse Comics’ Star Wars (2013) issues 17-20 (2014)

- Star Wars: Rebel Heist comic miniseries (2014)

- Star Wars: Jedi Academy series

- Star Wars: Legacy Volume 2 issues 15-18 (2014)

- Star Wars: Imperial Handbook: A Commander’s Guide (2014)

- Fantasy Flight Games’ RPG supplements, which blend both canon and Legends

- Star Wars: Graphics (2016)

- Star Wars: Visions TV series and its spinoffs

- The hundred and eighth issue of Marvel’s original Star Wars comic series (2019)

Canon Classification Within the Holocron Continuity Database

In 2000, Lucas Licensing tasked Leland Chee with creating the Holocron continuity database to track and classify Star Wars canon. Each element in the database received a letter grade: G, T, C, S, N, or D, representing the level of canonicity.

The letters were informally applied to different canon levels themselves: G-canon, T-canon, C-canon, S-canon, N-canon, and D-canon.

G-canon was the highest level, representing George Lucas’ vision of Star Wars. T-canon referred to television content, such as The Clone Wars. C-canon encompassed most works of the Expanded Universe, and S-canon represented secondary material, often older content. N-canon was reserved for non-canon material, and D-canon referred to the canceled Star Wars Detours animated series.

Over time, elements of the Expanded Universe were either elevated to C-canon or retconned to match newer G-canon material.

The Relationship Between Canon and Video Games

Some games have canonical storylines, while others are non-canon.

Sourcebooks written for Star Wars roleplaying games, like Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game by Bill Slavicsek, were considered part of the official canon maintained by Lucas Licensing.

However, in decision-based games like Knights of the Old Republic or Dark Forces/Jedi Knight, where players could choose between different outcomes, only certain storylines were considered canonical.

Many of these questions were left intentionally unresolved, though some were clarified in Legends material.

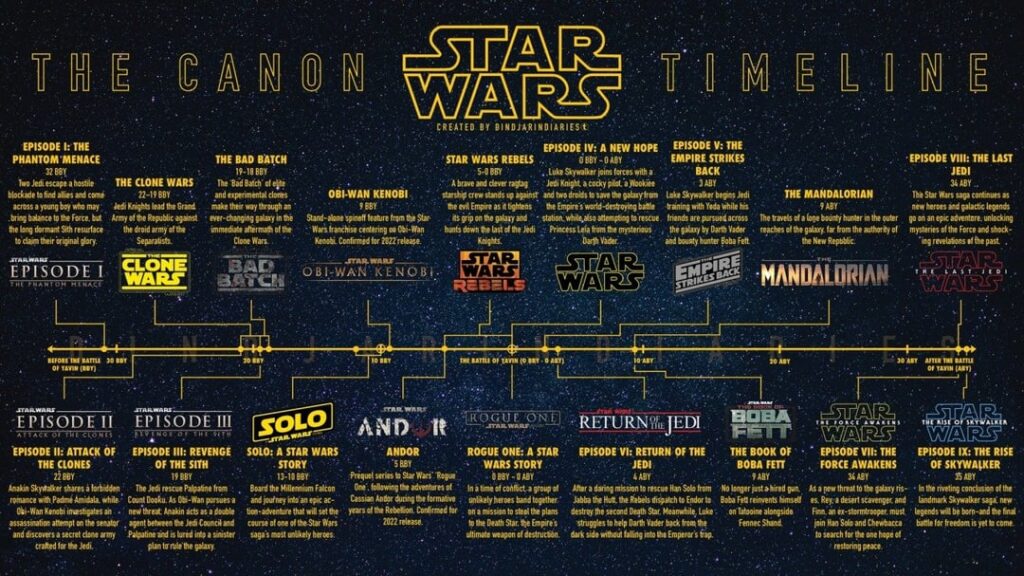

Star Wars Canon Timeline

Explore Our Lightsaber Collection

Tony Allen is a writer for LightsabersBlog.com, a website focused on everything related to lightsabers. Tony grew up in Austin, Texas, and went on to study Mechanical Engineering at the University of Texas. Passionate about science fiction and fantasy, Tony has always been deeply involved in hobbies like tabletop RPGs, sci-fi novels, miniature painting, and crafting. This love for creative pursuits drives Tony to write about lightsabers in a way that ignites the imagination of fans around the world.